- Home

- Evie Grace

Half a Sixpence

Half a Sixpence Read online

Contents

About the Book

About the Author

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgements

1830

Chapter One: The Bonnet

Chapter Two: The Harvest

Chapter Three: Laudanum and Smelling Salts

Chapter Four: The Watch

1833

Chapter Five: A Silver Sixpence

1837

Chapter Six: Smoking out the Bees

Chapter Seven: Hop Picking

Chapter Eight: Carrying the Anvil

Chapter Nine: Shooting at the Stars

Chapter Ten: Behold a White Horse

Chapter Eleven: The Battle of Bossenden

Chapter Twelve: The Red Lion

Chapter Thirteen: The Assizes

Chapter Fourteen: Innocence and Temperance

Chapter Fifteen: The Littlest Feet

Chapter Sixteen: This Little Piggy

1841

Chapter Seventeen: The Messenger

Chapter Eighteen: Least Said, Soonest Mended

Chapter Nineteen: Catch him Crow, Carry him Kite

Read on for an extract from Half a Heart

Copyright

About the Book

East Kent, 1830

Catherine Rook takes her peaceful life for granted. Her days are spent at the village school and lending a hand on her family’s farm. Life is run by the seasons, and there’s little time for worry.

But rural unrest begins sweeping through Kent, and when Pa Rook buys a threshing machine, it brings turbulence and tragedy to Wanstall Farm. With the Rooks’ fortunes forever changed, Catherine must struggle to hold her family together.

She turns to her childhood companion, Matty Carter, for comfort, and finds more than friendship in his loving arms. But Matty has his own family to protect, and almost as quickly as their love blossoms, their future begins to unravel.

With the threat of destitution nipping at her heels, Catherine must forge a way out of ruin…

About the Author

Evie Grace was born in Kent, and one of her earliest memories is of picking cherries with her grandfather who managed a fruit farm near Selling. Holidays spent in the Kent countryside and the stories passed down through her family inspired her to write Half a Sixpence.

Evie now lives in Devon with her partner and dog. She has a grown-up daughter and son.

She loves researching the history of the nineteenth century and is very grateful for the invention of the washing machine, having discovered how the Victorians struggled to do their laundry.

Half a Sixpence is Evie’s first novel in her Kentish trilogy. Half a Heart and Half a Chance will follow.

In memory of my grandparents who taught me resilience.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank Laura at MBA Literary Agents, and Viola and the team at Penguin Random House UK for their enthusiasm and support. I’m also very grateful to my mum for her help with researching Victorian Kent and sharing her memories of hop picking.

1830

Chapter One

The Bonnet

Overshill, East Kent

Catherine looked at the sea of golden corn in the field next to the stony road, and her heart soared. She gazed at the gently rolling countryside, a patchwork of hop gardens, orchards and meadows filled with wild flowers, then glanced at her companion.

‘There’ll be no school on Monday,’ she said.

‘Or the Monday after,’ Emily Millichip, the miller’s daughter, replied. She was heavily built with plump arms and ruddy cheeks, whereas Catherine was what other people described as delicate in appearance.

‘There’ll be no writing, reading or ’rithmetic.’

‘Or sewing, or taking a turn looking after the little ones.’ Emily was twelve years old, a year younger than Catherine, who was envious of the way Emily’s straw bonnet struggled to confine her blonde ringlets, while Catherine’s own dark hair hung long and wavy from under her bonnet, down to the small of her back.

‘Shall we go the long way through the woods?’ Catherine asked as they passed the end of the drive leading to Churt House, an imposing building with many windows and tall chimneys that stood on a rise looking down on the village of Overshill. She imagined taking off her boots and cooling her feet in the chalk stream that babbled through the vale below the village, but Emily wasn’t in the mood for dawdling.

‘I must go straight home,’ she said, looking towards the top of the hill ahead at the windmill with its four white sails and beehive cap set against tarred weatherboards. ‘Ma will give me a good hiding if I’m late.’

‘We’ll say Old Faggy kept us back to sweep the schoolroom floor.’ Mrs Fagg ran the dame school at Primrose Cottage for the village children whose parents were willing and able to pay for them to attend.

‘She’s bound to check with her when she comes to buy bread. Come on, let’s hurry.’ Emily took Catherine’s hand and they continued past the vicarage and the Church of Our Lady where they went every Sunday with their families. The church was built from grey ragstone with a red-tiled roof and stained-glass windows. It had a chapel to the side and a central tower which, according to Pa, the villagers had used as a lookout in the past. The main door was made from oak and was partly hidden from the road by the dark, forbidding yews that watched over the dead.

Catherine and Emily turned along the path where the flint wall bordering the churchyard came to an end and the ground opened up into rough scrubland with a leafy hedgerow of blackthorn and brambles to one side.

The smell of bad eggs assaulted Catherine’s nostrils as a grey-green stagnant pond overgrown with weeds and bulrushes came into view. She shivered. She’d never liked Ghost Hole Pond, even before Old Faggy had taught them about the reign of the Jutish kings when people and horses were sacrificed in its murky waters to secure a good harvest for the village. Sometimes as she grew near it, she fancied that she could hear the screams of the victims and the splashing as the horses plunged in their fight against the spirits who dragged them without mercy to their grave.

‘There’s Matty Carter,’ Emily said, pointing towards a boy of about fourteen who was striding towards them with a bag slung over his shoulder.

Catherine disapproved of his coarse manners and his raggedy clothes that reeked of hops and smoke, and she hadn’t liked the way he used to tease her at school.

‘He’s trouble. We must keep out of his way,’ she said, but it was too late. He stopped in front of them. His brown hair stood up on end like a stook of corn, the bridge of his nose was spattered with freckles and his cheek was smeared with dirt.

‘How’s Old Faggy?’ he asked with a glint of humour in his green eyes. ‘Does she miss me?’

‘She’s never said so.’ Catherine unhooked a stray bramble from her skirt.

Matty had left school the previous year, his income from work being more useful to his family than the education provided by an elderly spinster. Not that Old Faggy was a bad teacher. Pa set great store by her methods – she had taught him to read and write when he was a young man.

‘She probably didn’t notice me and Jervis were gone,’ Matty said, referring to one of his older brothers. There were seemingly endless Carter children, some still at home and others long grown up and moved away, but Matty had two older brothers who still lived in Overshill: Jervis, the eldest, who laboured on the farm when he wasn’t lurking on the Canterbury to London road, waylaying any unfortunates whose carriages had become stuck in the mud; and Stephen, the middle one, who was apprenticed to Overshill’s blacksmith. ‘She’s as deaf as an adder and blind as a bat.’

Catherine couldn’t help wondering if Old Faggy’s afflictions were more con

trived than real, her way of coping with the challenge of maintaining discipline in the classroom. What the eye didn’t see, the heart didn’t grieve over. If she did notice the older boys getting up to no good, flicking pieces of chalk at the girls, she would send them outside to chop wood.

‘Get out!’ she’d shout after them. ‘I don’t want none of you besoms in here.’

‘I never thought I’d say this, but now that I’m having to earn my living, I wish I was back at school,’ Matty said.

‘We don’t feel the same, I’m afraid. It’s a lot more peaceful without you,’ Catherine said. ‘What have you got in your bag?’

‘Nothing.’ Matty’s fingers tightened around the hessian sack.

‘You must have something. Show us.’ She reached out to take it, but he hugged it tight to his chest.

‘It’s none of your business.’ His eyes flashed with annoyance tinged with fear.

If, as a small boy, he hadn’t relished scaring the life out of her with slugs and slow-worms, or laughing at her when she filled her shoes as well as her bucket with water at the pump in the farmyard, Catherine might have backed down. But remembering the sensation of the mouse’s teeth nibbling at the back of her neck and the sheer panic as it slid between her skin and the fabric of her blouse while they sat in class at Old Faggy’s, she made up her mind.

She grabbed at the sack.

‘No, miss. Please don’t.’ Matty tore it from her fingers and threw it back over his shoulder, but it was too late. She knew what he’d been up to from the scent the hessian had left on her skin.

‘Leave him alone,’ Emily sighed. ‘He isn’t worth our notice.’

‘Where did you get them onions from?’ Catherine said.

‘I haven’t got no onions. I’ve bin collecting herbs for me ma.’

‘I can smell them.’ Catherine watched his face turn dark red like boiled beetroot. ‘Where did you get them from?’ she repeated.

‘I found them by the wayside.’ Unable to meet her gaze, he traced circles in the earth with his boot, showing off the scuffed leather patches across the toe.

‘You stole them,’ she said, shocked. ‘You took them from my pa, you thieving scoundrel.’ Her blood surged with fury at his betrayal of her father’s trust. Pa had a soft spot for the Carters, although she didn’t know why when none of them looked as if they’d ever had a wash in their lives. The Carter family rented the cottage at Toad’s Bottom, not far from Wanstall Farm where Catherine lived with her parents and brother John. Matty and Jervis worked for Catherine’s pa, who had also employed their father, George Carter, for as long as she could remember.

‘If I’d have picked up things I’d found just lying around, and they did belong to your pa, he wouldn’t notice as much.’

‘Of course he would.’ Pa counted each and every onion – that’s how he had made a success of the farm, and why Squire Temple showed his gratitude by keeping the rent the same year after year. He looked after the land, ploughed the straw and muck back into the ground, walked the fields to check on the crops, and sent the labourers out to pick the caterpillars and mildewed leaves off the hops. He knew every stone, every tree, every bird’s nest, every flower. ‘I’m going to make sure he hears about this.’

Matty lashed out and grabbed Emily’s bonnet from her head, as she was the closest to him. Catherine tried to snatch it back, but it was too late.

‘No,’ Emily cried. ‘Ma will have my guts for garters.’

Matty ran off and scrambled along one of the sloping branches that leaned across the surface of the pond. He stopped and balanced on his heels, holding the bonnet over the water.

‘Promise me you won’t tell,’ he called fiercely.

‘I shan’t promise anything,’ Catherine shouted back. In spite of her fears, she scooped up her skirts, petticoat and all, and started to climb along the branch. Emily’s ma had a temper on her and she didn’t see why Matty should involve her closest friend in their disagreement.

‘Please don’t.’ Emily grabbed at her arm. ‘He wouldn’t dare.’

Catherine freed herself from Emily’s grasp and pulled herself along the branch.

‘They call your pa “skinflinty Rook” at the beerhouse because of the niggardly wages he pays,’ Matty jibed.

‘He gave your pa a flitch of bacon and a sack of flour after the haymaking,’ Catherine countered. ‘You and your family don’t have to work for him. There are other masters.’ She glanced down at her sleeve which was covered with a dusting of lichen, and at the water below where the arms of the ghosts were outstretched to catch her and pull her into the depths. The branch trembled, making her perch seem even more precarious.

‘Listen.’ Matty’s eyes were wide with desperation. ‘I swear them onions were lying scattered across the ground, all round and swelled up. I seen them and I thought of my brothers and sisters and how they haven’t eaten anything but bread since Sunday night, and before I knew it, they were in the bag.’ A tear ran down his cheek. ‘I’m truly sorry, Miss Rook. Please don’t tell. If I’m dragged up in front of the magistrate, I’ll be locked up or hanged. My family will starve.’

Catherine didn’t like to think of the little Carters with their runny noses and dirty clothes dying from hunger, but surely Matty was exaggerating about the punishment. When his brother Jervis had been caught with apples in his pockets, he’d been whipped and sent on his way, laughing in the magistrate’s face.

‘I won’t keep secrets.’ She had been brought up to be open and honest. ‘Now, give me that bonnet, or else.’

‘Or else, what?’ Matty growled. ‘You’re going to tell on me whatever I say. I’m doomed.’

She watched his fingers slacken and the bonnet fall and spread across the surface of the water with the ribbons drifting behind it.

Emily screamed. Catherine snapped off a hazel twig and caught the bonnet, lifting it out of the water before she clambered carefully back to safety, leaving Matty sitting astride the branch with his head in his hands.

‘Ta.’ Emily took the bonnet by her fingertips as though it was stained with blood. ‘Oh no, it’s ruined.’ She started to cry.

‘Wring it out carefully and lay it across the bushes around the corner so it will dry in the sun,’ Catherine ordered. ‘You can have my bonnet and I’ll come back for yours later. That way your ma will never know.’ She didn’t look back. She placed her own bonnet on Emily’s head and fastened the ribbons, and, having done her best to dry her friend’s tears, they continued on their way along the path, turning left onto Overshill’s main street.

They passed a pair of black-and-white timber-framed houses before reaching the forge and its attached cottage where a pair of carthorses stood in the shade of the spreading chestnut tree, waiting to be shod.

Stephen Carter, dressed in a shirt, trousers and brown leather apron, was untying one of the horses from the iron ring that was buried in the tree trunk.

‘Hello, Miss Rook and Miss Millichip,’ he said shyly, touching his forelock of wavy brown hair. At seventeen, he was taller than Matty and his arms were all sinew and muscle. He rubbed at his side whiskers as if he had some kind of rash. ‘How are you today?’

‘We’d be much better if your brother hadn’t made off with Emily’s bonnet, thank you for asking,’ Catherine said.

‘I’m sorry. I’ll box his ears for you.’ He clenched his fist around the horse’s rope. ‘That’ll learn Jervis not to terrorise innocent young ladies on their way home from school.’

‘Oh, it wasn’t Jervis,’ Catherine said. ‘It was Matty. And please don’t trouble yourself on our account. We can stand up for ourselves, can’t we, Emily?’

Emily nodded, but Catherine wasn’t convinced. Emily’s ma had taught her to act helpless, not fight back when she was wronged.

‘Stop your cotchering and get that nag over here now, lad,’ yelled a voice from within the dark depths of the forge where the coals were burning brightly. ‘Have you finished sharpening those scythes? G

eorge will be here for them on his way back through. There’ll be hell to pay if they aren’t ready.’

‘I’d better go, or the master will be after me,’ Stephen said cheerfully. ‘I don’t know why he scolds me for gossiping when it’s he who can talk the hind leg off a donkey. Good afternoon.’

‘Len’s always shouting,’ Catherine said as she and Emily watched Stephen lead the horse away. Len was married to Catherine’s sister Ivy. He could be a bit grumpy, and she didn’t want to hang around. ‘Let’s go.’ She saw him emerging from the forge. ‘Hurry!’

‘Don’t you want to say hello to Ivy?’ Emily said. ‘You haven’t seen her for ages.’

Catherine shook her head. Ivy was much older than her and they didn’t have much in common. She never felt entirely welcome at Forge Cottage. When she did visit, Ivy would offer her a drink and something to eat, before returning to her needlework. She was a good seamstress and her services were much in demand in Overshill.

Catherine and Emily walked on past a terrace of brick cottages where the gardens were filled with pale pink and deep blue geraniums, bright sunflowers and the mauve spikes of buddleias clothed with butterflies and buzzing with bees. On the opposite side of the road was the butcher’s shop, then the greengrocer’s and the Woodsman’s Arms where a pair of elderly men in their smocks were sitting outside on a bench. They raised their tankards in greeting. Catherine nodded in return.

‘Stephen is very polite, don’t you think?’ Emily observed.

‘He isn’t at all like his brother. They’re like chalk and cheese.’

‘I thought you should have been at least a mite grateful to him, considering that he made so bold as to offer to box Matty’s ears. Do you remember how he hardly spoke to us when he was at school?’

‘I didn’t take much notice of him,’ Catherine said.

‘I wouldn’t say no to Stephen Carter if he should ask me to marry him one day,’ Emily went on. ‘He’s very handsome.’

‘Ma would absolutely forbid me to walk out with any of the Carter brothers. She’s devoting her spare time to making sure that I marry up.’ Catherine pursed her lips and twirled an imaginary parasol as if she was a lady. Laughing, Emily joined in and they danced the rest of the way up the hill past the oast house, an old barn with a round kiln tacked on to the end for drying the hops in September. The wheelwright was perched on a ladder that was leaning between the barn roof and the kell so that he could repair the white-painted cowl on the top.

The Seaside Angel

The Seaside Angel A Thimbleful of Hope

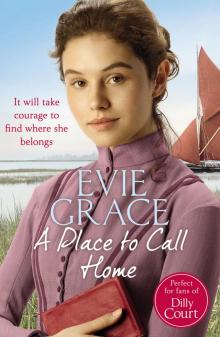

A Thimbleful of Hope A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Her Mother's Daughter

Her Mother's Daughter Half a Sixpence

Half a Sixpence