- Home

- Evie Grace

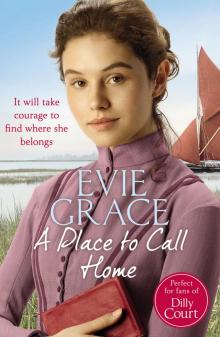

A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Read online

Contents

About the Book

About the Author

Also by Evie Grace

Title Page

Dedication

1876

Chapter One: A Patchwork Family

Chapter Two: Making the Ordinary Extraordinary

Chapter Three: St Lubbock’s Day

Chapter Four: The Power of Love

Chapter Five: Ostrich Plumes and Silver Trappings

Chapter Six: The Last Will and Testament

Chapter Seven: The Weeping Willows and Grey Stones of the Westgate

Chapter Eight: The Best Way Forward

Chapter Nine: Cod Liver Oil and Malt

Chapter Ten: Aspidistras and Apple-Pie Beds

1876–1877

Chapter Eleven: An Ill Wind Blows Nobody Any Good

Chapter Twelve: Roly-Poly Pudding and Custard

Chapter Thirteen: Overshill

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen: Work for Idle Hands

Chapter Sixteen: The Gentleman Who Pays the Rent

1878

Chapter Seventeen: Mighty Oaks from Little Acorns Grow

Chapter Eighteen: Don’t Look a Gift Horse in the Mouth

1879

Chapter Nineteen: Let the Punishment Fit the Crime

Chapter Twenty: Like a Flea on a Dog

Chapter Twenty-One: Up the Creek

Chapter Twenty-Two: Gentleman or Rogue?

Chapter Twenty-Three: As the Crow Flies

Chapter Twenty-Four: A Full Sixpence

Chapter Twenty-Five: The Truth Will Out

Chapter Twenty-Six: Nothing Ventured, Nothing Gained

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Book

THE THIRD AND FINAL SAGA IN EVIE GRACE’S MAIDS OF KENT TRILOGY.

East Kent, 1876

With doting parents and siblings she adores, sixteen-year-old Rose Cheevers leads a contented life at Willow Place in Canterbury. A bright future ahead of her, she dreams of following in her mother’s footsteps and becoming a teacher.

Then one traumatic day turns the Cheevers’ household upside-down. What was once a safe haven has become a place of peril, and Rose is forced to flee with the younger children. Desperate, she seeks refuge in a remote village with a long lost grandmother who did not know she existed.

But safety comes at a price, and the arrival of a young stranger with connections to her past raises uncomfortable questions about what the future holds. Somehow, Rose must find the strength to keep her family together. Above all else, though, she needs a place to call home.

About the Author

Evie Grace was born in Kent, and one of her earliest memories is of picking cherries with her grandfather who managed a fruit farm near Selling. Holidays spent in the Kent countryside and the stories passed down through her family inspired her to write her Maids of Kent trilogy.

Evie now lives in Devon with her partner and dog. She has a grown-up daughter and son.

She loves researching the history of the nineteenth century and is very grateful for the invention of the washing machine, having discovered how the Victorians struggled to do their laundry.

A Place to Call Home is the third and final novel in the Maids of Kent trilogy, following on from Her Mother’s Daughter.

Also by Evie Grace

Half a Sixpence

Her Mother’s Daughter

To Tamsin and Will

1876

Chapter One

A Patchwork Family

‘You look well, my dear Rose.’

As Aunt Marjorie spoke the marble clock on the mantel in the dining room chimed four. It was a warm summer’s afternoon and the sunshine had roused the dumbledores into a frenzy on the fragrant honeysuckle outside the half-open window.

Rose caught a glimpse of her reflection in the mirror. She had pinched her cheeks to add some colour to her complexion and bound her dark brown hair up to the back of her head in a heavy plait.

‘I’ve always said she’s quite the aristocrat,’ Aunt Temperance joined in as they stood waiting to be seated. ‘With those cheekbones and striking blue eyes she could easily pass as a baronet’s daughter.’

Rose turned towards her tall, brown-eyed father who was giving his sister a look, meaning don’t give her ideas above her station.

Dear Pa, she mused fondly. He was the head of their family, their rock. Rose considered him a very handsome man for his age, with his loose curls of dark hair, side-whiskers and beard, run through with sparse strands of silver.

‘I remember the day you were born, Rose,’ Aunt Marjorie said. ‘The most angelic child has grown into a refined young lady. How time flies!’

Sixteen years had passed since her parents had blessed their tiny infant with the name of Rose Agnes Ivy Catherine Cheevers. She didn’t know what they’d been thinking of, but her parents said that they were family names and it was important to keep them alive. Her elder brother was plain Arthur Cheevers, and her younger siblings had but two forenames each.

‘I’m sorry that Mr Kingsley couldn’t join us,’ Pa said. Mr Kingsley was Aunt Temperance’s husband, and Rose’s uncle, but no one ever called him anything but Mr Kingsley.

‘He is sadly indisposed.’

This was Aunt Temperance’s usual response. Rose smoothed the front of her new dress made from pale muslin decorated with woven pink and green sprays of flowers. She knew that Mr Kingsley was more than likely to be in one of the local taverns.

‘It is unfortunate that he is some years my senior and not in the best of health,’ Aunt Temperance went on.

‘He is a little liverish again, I expect,’ Aunt Marjorie said with a wicked glint in her eye.

‘He is suffering from a touch of gout,’ Aunt Temperance responded sharply.

‘An affliction worthy of our sympathy. You must convey our best wishes for a full and prompt recovery – I hope to see him in the office as usual on Monday,’ Pa interrupted as Rose’s younger sister, Minnie, entered the room, her face flushed from the heat. ‘Please, do sit down.’

As the aunts took their places at the table, Rose watched and waited.

The dining room at Willow Place was roughly square, the outer wall sloping out at an angle as though, like Mr Kingsley, the builder had partaken in too much liquor when erecting the timber frame for the wattle and daub infill. The window with its diamond leaded lights was set deep into the wall, and an oak bookcase stood alongside it, crammed with leather-bound tomes on subjects ranging from natural history to travel and exploration, and Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, The Lady of the Lake and his Waverley novels. On top of the bookcase was a stuffed pike that Pa had caught from the river, and a medal presented to him by the dignitaries of Canterbury for rescuing two men from drowning.

Rose often wondered how Pa had felt risking his life in the filthy waters of the Stour.

‘Rose,’ Aunt Temperance said, jolting her from her reverie, ‘you would do well to remember in future that there is nothing wrong in marrying an older man – he is more likely to be settled in his preferences, financially solvent and grateful. It helps, of course, if it is a love match.’

Rose didn’t know how to respond. Family folklore said that her aunt had chosen her husband because she had thought the name Kingsley a great improvement on Cheevers. Rose couldn’t help thinking that Aunt Temperance, who was two or three years older than Pa, could have done much better for herself. According to Ma, she had been quite a beauty, with delicate features and chestnut hair.

Aunt Marjorie was in her fifties and had never married. Rose wondered if it was because she was rather plain. She had hair of silver and sienna, wore serge skirts and horn-rimmed spectacles that k

ept slipping down her nose.

‘Sit down, Rose,’ Pa said, gesturing towards the far side of the table where he had suspended a plank between two of the stick-back dining chairs to provide an extra perch.

She moved round and sat down on one of the chairs on which Pa had placed a cushion for extra padding. Minnie took the other chair and left the plank for Donald. The aunts sat opposite with Arthur between them, while Ma and Pa sat one at each end of the table. Arthur had stuck his forelock of sandy blond hair to his forehead with Pa’s Macassar oil.

From Rose’s vantage point, she could see the globe, a beautifully decorated map of the world on a stand in the corner of the room. Pa had bought it as a present for Ma, but she had judged it too fine to be exposed to her pupils’ grubby fingers and had instead kept it in the house. Some evenings, she wheeled it on its castors into the parlour and made a game of finding the different parts of the British Empire, naming their capital cities.

She glanced towards Arthur who rolled his eyes in her direction. She smiled, sympathising for his plight.

‘Arthur, dear boy, you seem a little out of sorts,’ Aunt Marjorie observed, although he was a young man of twenty-three, not a boy any more.

‘He is missing his sweetheart,’ Ma said cheerfully. Her mouth was wide, her nose small, and she was beginning to run to fat. Sometimes her eyes looked green, sometimes hazel, depending on the light. She had tied her greying hair back, which had the effect of making her look rather austere. ‘I told him he must spend some time with us for a change. He will have plenty of time with her when they are married.’

‘I can speak for myself, Ma,’ Arthur countered.

‘He will go out later,’ Minnie chuckled. ‘He’s oiled his hair. Look how it glistens. And he is wearing his Sunday best on a Saturday.’

‘Do I hear the sound of wedding bells?’ Aunt Marjorie said, smiling, and Arthur blushed.

‘You have been walking out with the apothecary’s daughter for over a year,’ Aunt Temperance said. ‘Mind she doesn’t tire of you.’

‘Leave the young man alone. Marry in haste, repent at leisure. There’s no rush. You need to be sure that you can face Miss Miskin every day for the rest of your life, treating her with love and respect and without wearying of her.’ Pa looked fondly at Ma who smiled in response. Rose couldn’t imagine her parents ever tiring of each other’s company.

‘I can’t see any reason to delay once one has made the decision to enter the state of holy matrimony,’ Aunt Temperance said.

‘If you must know, we’ve been saving up for our future,’ Arthur said.

‘I’m delighted to hear it. Miss Miskin is a very lucky woman. You will make an excellent husband.’ Rose couldn’t help feeling that Aunt Marjorie was aiming this comment at Aunt Temperance, who pursed her lips as if she was sucking a lemon. Aunt Marjorie wasn’t their aunt by blood, but Pa’s cousin once removed. It wasn’t her only connection to the family – she had once been Ma’s nanny and governess. She’d aged considerably since she’d last visited Willow Place, and Rose couldn’t see how she could manage to care for her current employer’s children with her stoop, shuffling gait and stiff fingers.

‘I love a good wedding,’ Aunt Marjorie sighed.

‘Where is Donald?’ Ma changed the subject abruptly.

‘Have you seen your brother recently?’ Rose asked her little sister, except that Minnie wasn’t little any more. She was twelve and growing fast with dark brown eyes like Pa’s and hair that fell around her shoulders in soft blond ringlets.

‘Why is he always my brother, not ours, when he’s in trouble?’

‘I told him not to be late – I’ll have his guts for garters,’ Ma said.

‘I hope he’s here soon. I’m looking forward to my tea,’ Aunt Marjorie said.

‘I’ll go and find him,’ Rose offered.

‘Arthur should go, but thank you, Stringy Bean,’ Pa said before lowering his eyes in apology for calling her by her pet name in company.

‘Where can he be?’ Aunt Marjorie asked just as an object came flying through the window. Minnie screamed as it whistled past her ear and landed in the middle of Rose’s plate. Pieces of china flew in all directions and the object – a dark red ball – rolled to a stop in front of her. She grasped it and held it up, the leather smooth under her fingertips.

‘’Ow is that!’ said Arthur.

‘Donald!’ Pa stood up and roared through the open window. ‘Get yourself indoors this minute!’

‘Be gentle with him, Oliver,’ Ma said. ‘I’ll make sure he pays for what he’s broken. I’m sorry for his behaviour, but boys will be boys.’

‘There is a balance to be struck between allowing children to express themselves in order to develop their characters, and spoiling them, Agnes,’ Aunt Marjorie said, taking Pa’s side.

‘Indeed,’ Aunt Temperance agreed and Rose wondered how she knew when she had no children of her own. Aunt Marjorie had none either, but she had had plenty of experience of bringing up other people’s offspring.

‘I would make an example of him if he were mine,’ Aunt Temperance opined. ‘A beating would soon l’arn him to stop his impetuous ways.’

‘I’m not a believer in corporal punishment,’ Pa said firmly. ‘The expectation of a good hiding makes one more apprehensive of a repeat performance, but it doesn’t address the cause of the problem.’

‘Well, that boy is trouble. He’s already in training for the treadmill and oakum shed.’

‘Oh, Temperance,’ Ma sighed. ‘You do exaggerate. He’s in high spirits, that’s all. He knows very well the difference between right and wrong.’

Donald was slow to answer Pa’s call. Eventually, he sauntered into the dining room, wiping his hands on a white shirt that sported several grass stains. He was Minnie’s twin, and the younger one by virtue of having followed his sister into the world two hours behind, after midnight. Minnie was born on Tuesday, and, as the rhyme said, was full of grace, while Donald, born on Wednesday, was full of woe, although Rose felt that it was truer to say that Donald could create woe wherever he went.

‘Well, what do you have to say for yourself?’ Pa barked from where he sat in the oak carver at the head of the table.

Donald looked at him sheepishly, gazing through a fringe of sandy-coloured curls. ‘I’m sorry, Father. Joe and I were practising.’

Joe was one of Donald’s friends. Rose had thought of him as a calming influence, but now she wasn’t so sure.

‘If it wasn’t for the presence of your mother and aunts, I would banish you to your room. Rose, give me the ball, please.’

Rose handed it over, aware of Donald’s frown of disapproval as Pa turned and placed it carefully in the bonbon dish that stood on top of the dark oak court cupboard, a hefty, Gothic-looking piece of furniture which used to belong to Pa’s grandfather.

‘When shall I be allowed to have it back?’ Donald asked, his brow furrowed.

‘When you’ve cleared the broken plate and paid for a replacement.’ Pa smiled ruefully. ‘Mr W. G. Grace has much to answer for.’

‘He is becoming a legend in his own lifetime,’ Aunt Marjorie said. ‘I’ve read that he’s the first man to pass a thousand runs and a hundred wickets – that must have been last year.’

‘He’s a giant,’ Donald said, his eyes filled with admiration. ‘Literally.’

‘I’ve heard that he’s a large man with a fair bird’s nest of a beard, but I don’t hold with cricket,’ Aunt Temperance cut in. ‘It’s a game that’s played by any Tom, Dick and Harry on the streets, and a complete waste of time. I don’t know how many winders have been broken around here because of it.’

‘It’s become the sport of gentlemen,’ Ma said, putting on a cut-glass accent.

‘When will we expect to see you playing at the Beverley Ground?’ Aunt Marjorie asked.

‘As soon as I’m old enough. There’s a lime tree there and I’m going to be the first cricketer to clear the tree to score a six.’ Do

nald tweaked the braces holding up his brown moleskin trousers as he moved round to sit with his sisters. The plank creaked ominously with the extra weight and Rose moved as far away from him as possible. She admired his ambition, but his clothes reeked of perspiration and a hint of the tan yard.

‘What’s for tea? I’m starving,’ he whispered, his dark brown eyes settling on the slices of fresh bread, cheese and jars of pickled onions, eggs and cucumbers. A grin spread across his face. ‘Oh, I can guess.’

‘We thought we would have ox tongue for a change,’ Ma said, straight-faced.

Rose glanced at her Aunt Marjorie, whose expression changed from joyful anticipation to consternation. Rose was confused, too, because she knew that Mrs Dunn, the housekeeper, had bought a pig’s head and soaked it in brine – she had shown Rose how to check the strength of the solution by floating a potato in it. Then she had drained the head, put it into a stew-pot with the ears, some chopped onions and herbs, covered it in cold water and brought it up to the boil, simmering it for hours and skimming off the scum, until the meat fell from the bone. She had let it cool, chopped the meat, added parsley and stirred it together with a little of the cooking liquor before placing it in a mould with a muslin and brass weights from the kitchen scales on top.

Rose remembered how there had been some discussion between Ma and the housekeeper about the best way of keeping it cool, the pantry being considered too warm. It had been placed in the cellar, but perhaps that hadn’t been right for it either. Had the brawn failed to set?

‘There is no brawn?’ Aunt Marjorie enquired.

‘I’m afraid that it’s gone off.’ Rose caught Ma smiling at Pa.

‘That is a disaster. Oh, what a terrible shame.’ Aunt Marjorie sounded distraught.

‘Do not distress yourself,’ Pa said, chuckling. ‘Of course, there is brawn.’

‘Thank goodness,’ Aunt Marjorie sighed. ‘I’ve been so looking forward to it.’

‘It’s the only reason she calls on us,’ Donald whispered.

‘Hush.’ Rose nudged him with her elbow. It wasn’t true.

The Seaside Angel

The Seaside Angel A Thimbleful of Hope

A Thimbleful of Hope A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Her Mother's Daughter

Her Mother's Daughter Half a Sixpence

Half a Sixpence