- Home

- Evie Grace

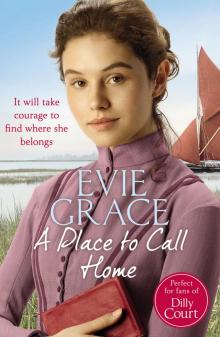

A Place to Call Home Page 2

A Place to Call Home Read online

Page 2

‘I will do the honours,’ Pa said, getting up from his seat and disappearing from the room. He returned shortly afterwards, carrying a plate on which sat the trembling mound of brawn. He placed it in front of him, took up the carving knife and fork and began to slice it, the blade slipping through it as if it were butter.

‘Pass your plates. Ladies first, Donald,’ he said as Donald raised his platter.

The maid, dressed in her dark uniform and pristine white apron, came into the room with a replacement plate for Rose. Jane was eighteen and had been at Willow Place for six months. She was tall and slender with long, pale blond hair plaited and coiled beneath her cap. Ma and Mrs Dunn had found her to be kind, hard-working and quick to learn, and the family were already quite attached to her.

Once the brawn was served, they sat waiting for Jane to finish pouring the lemonade and beer into their glasses. Rose could hear Donald’s stomach rumbling. She could see Aunt Marjorie’s fingers hovering over her cutlery as she tried to restrain herself.

‘Thank you, Jane. That will be all for now,’ Pa said.

Jane gave a small curtsey – Pa had tried in vain to train her out of the demeaning habit which she’d learned at her previous place – and left the room.

As Pa said grace, Rose noticed how Donald’s eyes darted furtively around the room. She wondered what he was thinking, what he was plotting next.

‘Amen,’ she said, joining in with the others. Aunt Marjorie’s fingers made contact with her knife and fork, but flew off again when Pa said jovially:

‘I believe that a toast is in order. We’re very pleased that you have chosen to spend some of your precious annual holiday with us, Aunt Marjorie. And I’m delighted you were able to grace us with your presence, Temperance. Let’s raise a glass and drink to health and happiness, and the jolliest of times.’

‘To health and happiness,’ Ma echoed.

‘And the jolliest of times,’ Pa repeated, beaming widely as he drained his glass.

‘Thank you very much for your hospitality. It’s lovely to be back in the family fold, albeit for a brief visit,’ Aunt Marjorie said before Pa finally released her from her misery, saying, ‘Let’s eat.’

Rose helped herself to bread and butter and a pickled onion before trying the brawn. It was delicious, the meat soft and flavoursome and the jelly succulent. Aunt Marjorie could certainly tuck it away, she thought as she watched Pa serve her a second helping.

‘The sea air seems to agree with you, Marjorie,’ Ma said eventually. ‘How are your charges in Ramsgate?’

‘They are well, thank you, although I find it more tiring chasing after them now – I’m not getting any younger. Occasionally I think of retiring, but I enjoy being a governess too much to give it up just yet, and besides, what would I have to talk about? I can’t imagine myself settling to a daily routine of a little light gardening and games of Patience.’

‘It’s a shame that one has to work to make oneself interesting,’ Aunt Temperance observed.

‘How is the school, Agnes?’ Aunt Marjorie went on, ignoring the slight.

‘It’s much the same,’ Ma said. ‘Rose is a willing and able pupil teacher.’

‘Thank you,’ Rose said, her cheeks growing warm at Ma’s compliment.

‘She will be ready to take it on when I retire,’ Ma said.

Rose felt awkward on hearing the pride in her mother’s voice. She liked teaching the younger children, but she didn’t see education as her future. She would like a husband and family of her own, and it would take a very special man to allow his wife to work instead of keeping house, as Pa did with Ma. Equally, she didn’t want to end up on the shelf like her spinster aunt.

‘Tell me, Oliver, how is business at the tannery?’ Aunt Marjorie asked.

‘Ah, life is good. The leather market is as buoyant as a cork – the butts are selling more briskly than ever.’ Pa grinned and Rose smiled back. ‘Our leather is always in great demand, and only yesterday, I met with two potential new customers. In fact, I’m looking to increase the supply of hides as a consequence. We can’t depend on our local suppliers to keep pace with our requirements.’

‘Mr Kingsley says that the availability of imported hides threatens to wreck the home market,’ Aunt Temperance said.

‘I have no issue with it. I’ve heard that the hides from Argentina are bigger and of better quality than those I can get here. Our grandfather would have embraced change if it was for the good of the business.’ Pa smiled again. ‘I’ll never weary of seeing the butts lifted out of the pits and hung up to dry until they’re ready to be made into boots fit for our beloved Queen Victoria, and portmanteaux fit for gentlemen.’ He looked at Minnie and Rose, his expression suddenly stern.

‘Remember, my dears, that there are true gentlemen and then there are those who purport to be gentlemen.’

‘How do you tell the difference, Pa?’ Rose asked.

‘Well, it isn’t as simple as looking at the label on his luggage to see where it was made and by whom. Having the means to purchase a luxury item made by royal warrant is no guarantee of a person’s manners and character. You have to observe how he interacts with his acquaintances and treats his servants. You have to take time to dig deep and find out what’s really in his heart.’

‘Well said,’ Aunt Marjorie exclaimed, clasping her hands together.

‘They are wise words,’ Aunt Temperance agreed. ‘I disagree, though, on using one’s attitude to one’s servants as a measure of manners. One shouldn’t treat servants as friends. There should always be a respectful distance maintained between employer and maid.’

‘They are people, made from the same flesh and blood as anyone else,’ Ma said. ‘I shall treat our servants as I see fit. I must be doing something right, mustn’t I? Mrs Dunn has been housekeeper at Willow Place since Evie left.’

‘How long ago was that? Remind me,’ Aunt Marjorie said.

Ma paused to think for a moment. ‘Evie married and moved away to be nearer her family when Rose was about three, if I remember rightly. We’re still in touch.’

Rose had a vague recollection of their previous housekeeper, a kind woman who had spoken with a country accent.

‘Please may I trouble you for a little more brawn?’ Aunt Marjorie asked.

‘Of course.’ Pa served her two more slices. ‘Minnie?’ The brawn was soon demolished.

‘Mrs Dunn has done us proud,’ Aunt Marjorie said, scraping her plate.

‘What shall we do tomorrow after church?’ Pa asked, changing the subject and reminding Rose that her aunt was staying for two more nights before returning to Ramsgate by train.

‘Oh, you must come with us to worship at the cathedral,’ Aunt Temperance said. ‘You don’t want to go to St Mildred’s. Oliver, I have no idea why you continue to frequent that church when you have your position to maintain.’

‘What position?’ Pa said, trying not to smile.

‘You are an esteemed member of society – look at your medals and the recognition you’ve received for your charitable deeds – your work for the Sanitary Society, for example. You should make the most of it.’ Her voice rose with excitement. ‘You could end up an alderman of the city, even mayor.’

‘I like St Mildred’s. It’s where our grandfather worshipped and where he took us every Sunday when we were younger and before you got this bee in your bonnet about the cathedral. I feel welcome there. One may worship wherever one feels close to God.’

‘Oh, suit yourself.’ Aunt Temperance shrugged her bony shoulders. ‘You are a fool.’

‘And you are misguided in thinking that I would seek fame in return for my services to the poor and disadvantaged in our society,’ Pa said a little sharply.

Arthur started to choke. Ma patted him on the back and he coughed up a pickled onion.

‘You two are like Minnie and Donald, always bickering,’ Ma observed cheerfully. ‘Let’s have some cake. Mrs Dunn has been busy baking.’

Their att

ention turned to fruit cake with almonds, cups of tea and the gifts Aunt Marjorie had brought for their curiosity cabinet in the parlour at Willow Place. She fetched them from her luggage and passed them around the table: a tiny silver thimble; a jar of shells; a fine geode filled with rose quartz crystals. She brought sweets too, rose rock and mint drops, which they shared between them.

Pa always said they were a patchwork family stitched together by circumstance, and people could say what they liked about them because there was nothing wrong in that. The presence of her aunts, sparring like two gamecocks, their words like spurs, reminded Rose that they were a happy family, but no ordinary one.

Chapter Two

Making the Ordinary Extraordinary

Aunt Marjorie went back to Ramsgate and life returned to normal. On the first Monday morning of July, Rose was standing in the hall at Willow Place, waiting for Donald as she had on so many other Monday mornings in the past.

Minnie would never win a prize for attendance, nor would Donald win one for punctuality, she thought. He had disappeared after breakfast with Pa and Arthur while Ma had gone ahead to open the school. Eventually she gave up on him and went into the parlour to say goodbye to Minnie.

‘Donald is green with envy,’ Minnie said from the window seat where she was sewing buttons on to one of Arthur’s shirts. ‘He wishes Ma had given him the day off school.’

‘He’s a lazy tyke,’ Rose said. ‘Minnie, what’s wrong with you? Are you in pain?’

‘Ma said I looked peaky. She thought it best that I had a day off, although for my sins, she has left me with a pile of mending and socks to darn.’

Minnie had given them many frights: the ague, quinsy and croup. She had always been delicate, more fragile than the rest of them, and a little slow of thought, a feature that Ma had mourned for many years. Rumour had it that she had been dropped on her head on the day she was born. Rose suspected that it had been one of those mysteries created by families to cover up a weakness, a difference. No one had actually confessed to dropping her. Had it been Ma, under the influence of the chloroform she had been given for the pain of childbirth? Or had the doctor been so busy looking out for Donald that he had omitted to take proper care of Minnie?

‘Is Ma going to send for the doctor this time?’ Rose asked, throwing a shawl over her modest blue dress and tying the ribbons of her bonnet.

‘I told her she mustn’t.’

‘And I concur,’ Rose smiled as she fastened the buckles on her fine leather shoes. The last time Doctor Norris had attended her sister, he’d diagnosed lack of blood and costiveness. The cure for the former was a diet of meat and for the latter, a weekly laxative purgation. It was no wonder Minnie didn’t want to see him again.

Rose left her sister threading her needle. She walked out of the house and down the drive, glancing back briefly at the black and white timber-framed building. Willow Place had three storeys stacked unevenly on top of one another, giving the impression that they might topple over at any moment.

Rose crossed the street into the yard, passing the sign that read in freshly painted gold lettering on black: Cheevers’ Tannery: Estd 1798 for the best leather, natural and dyed. Enquire within, and slipped in through one of the high gates which had been opened for deliveries.

Two workers, dressed in stained leather aprons and carrying pipes and tea cans at their waists, were unloading hides from a cart, sending up clouds of flies. Rose pressed a handkerchief to her nose. She had never become completely accustomed to the smells and sights of Pa’s business.

Treading carefully across the slippery stones, she caught sight of Arthur who was tipping a bucket of powdered bark into one of the pits. Donald was there too, stirring the bark into the water with a wooden pole a head taller than he was.

‘Donald,’ she called. ‘It’s time you weren’t here.’

He paused, looked up and gave her a rueful grin.

‘Donald!’ she repeated more forcefully.

He laid down the pole and ambled across to her with his hands in his pockets.

‘Arthur said I could help him today,’ he muttered as she gently cuffed his ears.

‘Well, he shouldn’t have done,’ she said loudly for her elder brother’s benefit.

Arthur glanced at her, a glint of humour in his eyes.

‘Give the lad a break.’

‘You know what Ma says. The three R’s come before anything else.’

‘I can read and write, and recite my times tables,’ Donald said. ‘In’t that enow?’

Rose frowned at him and he quickly reverted to the Queen’s English.

‘I’m twelve years old and I’m ready to work all hours like Pa and Arthur here,’ he went on.

‘I think Ma places too much store by it,’ Arthur contributed. ‘I can’t see the point in l’arning unless it serves a purpose. I’ve never been asked to multiply seven hides by seven, for example. Although I’m sure Pa would appreciate it – if it were physically possible.’ He chuckled.

‘You see. Arthur agrees with me,’ Donald piped up.

‘You’re both wrong.’ Rose shared Ma’s view that you never knew when you might need a little learning. Her eyes settled on Donald’s collar. ‘Look at your shirt. It’s filthy.’

‘Who cares when I have to mix with the maggoty boys at school?’ he said, setting his mouth in a stubborn straight line.

‘You mean the boys from the Rookery? Baxter and his brothers?’

Donald nodded.

‘You mustn’t speak of them like that,’ Rose said.

‘It’s the truth.’

‘They are boys, the same as you, but they haven’t had much luck.’ Rose knew that their mother was a lunatic and their father was struggling to keep them fed and clothed with his meagre takings as a bone-picker and rag-gatherer.

‘You must go to school to learn to be kinder, Donald,’ Arthur said softly. ‘I remember being like one of those boys, starvin’ and without hope. I started work when I was seven, helping my dearly departed mother by collecting and delivering laundry, cutting the trimmin’s from the hides here at the tannery and selling them on, and running errands for the Spodes.’

‘Who were they? I don’t recognise the name,’ Rose said, shading her eyes from the sun.

‘They were screevers. They had years conning money out of innocent people with fakements and petitions, signed with false names. Anyway, what I’m trying to say is that if it hadn’t been for Ma and Pa taking me in when my real ma passed, who knows what would have happened to me?’

‘I’m sorry,’ Donald said, apparently contrite. He did have a heart, Rose thought fondly. He just found it harder than some to show it.

‘My older brother Bert started out the same before Pa gave him a proper job as a tanner.’

‘What happened to him then?’ Donald said, squinting.

‘He’s a few years older than me. There was some kind of trouble and he went to London to make his fortune out of bricklaying,’ Arthur said wistfully.

‘Did he succeed?’ Donald asked.

‘I think he must have done very well for himself with all the building works going on, but I haven’t heard from him – he isn’t one for writing letters.’

‘I’m sure that I’d make my fortune if I went to London,’ Donald said, rather too full of his self-importance. Ma spoiled him, in Rose’s opinion, or maybe being the youngest of the Cheevers family, he felt that he had to make himself noticed.

‘There’s no need for you to go running away to London, or anywhere else,’ Rose scolded him. ‘You and Arthur will end up running the business—’ After Pa has gone, she was going to add, but that seemed an impossible thought. ‘Come along.’ She held out her hand, but Donald didn’t take it. He was too old for that now, she thought with regret. She had helped Ma bring the twins up since they were infants and couldn’t count how many times Donald had linked his sticky fingers through hers. ‘Quickly.’

‘I’ll see you both later.’ Arthur picked up th

e pole that Donald had laid down. ‘I’d better stir my stumps.’

‘So you had. Never a truer word has been spoken.’

Rose turned at the sound of Pa’s deep guffaw. He was striding across the yard towards them, wearing a white coat over his suit.

‘Oh, here’s the gaffer,’ Arthur said. ‘Morning, Pa.’

‘What’s all this? Shouldn’t you and Donald be at the schoolhouse by now?’ their father went on, addressing Rose.

‘I’d have been there already if it wasn’t for this one.’

‘You’ve been of great help, Donald, but it’s time you left,’ Pa said. ‘Arthur, I need you in my office – I’d like you to sit in on this morning’s meeting with Mr Kingsley and the agent who’s calling to discuss the supply of hides from Argentina. Off to school, you two.’

‘I suppose we have to,’ Donald sighed.

‘Yes, we do,’ Rose said firmly, and they made their way back across the yard to the gates.

As they headed along the street, Donald – fearing Ma’s wrath – ran off around the corner towards number 4 Riverside, one of the terraced cottages that belonged to the tannery. Rose followed him, but the sound of conversation caught her ear.

A woman’s voice drifted from a narrow passageway between two of the unkempt houses on the far side of the road.

‘I’ve always found it odd that a wife goes out to work when she has a husband who makes a good living.’

‘If I were her and I had the chance of being a lady of leisure, I’d take it,’ came another voice.

‘She should be at ’ome with ’er children. That boy of theirs has been allowed to run riot on the streets for years. ’Is parents are far too soft on ’im.’

‘Perhaps Mrs Cheevers don’t want to spend more time than is necessary with ’er husband.’

‘Oh, I don’t know about that. He’s a handsome man with a fine countenance.’

‘Don’t let ’er hear you say that, Mrs Couch. She’s an uncommon woman,’ said the other.

‘Do you mean rare in respect of being employed, or refined? For she is most respectable in her appearance and manners, and she speaks like a lady.’

The Seaside Angel

The Seaside Angel A Thimbleful of Hope

A Thimbleful of Hope A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Her Mother's Daughter

Her Mother's Daughter Half a Sixpence

Half a Sixpence